By Danielle Bonior

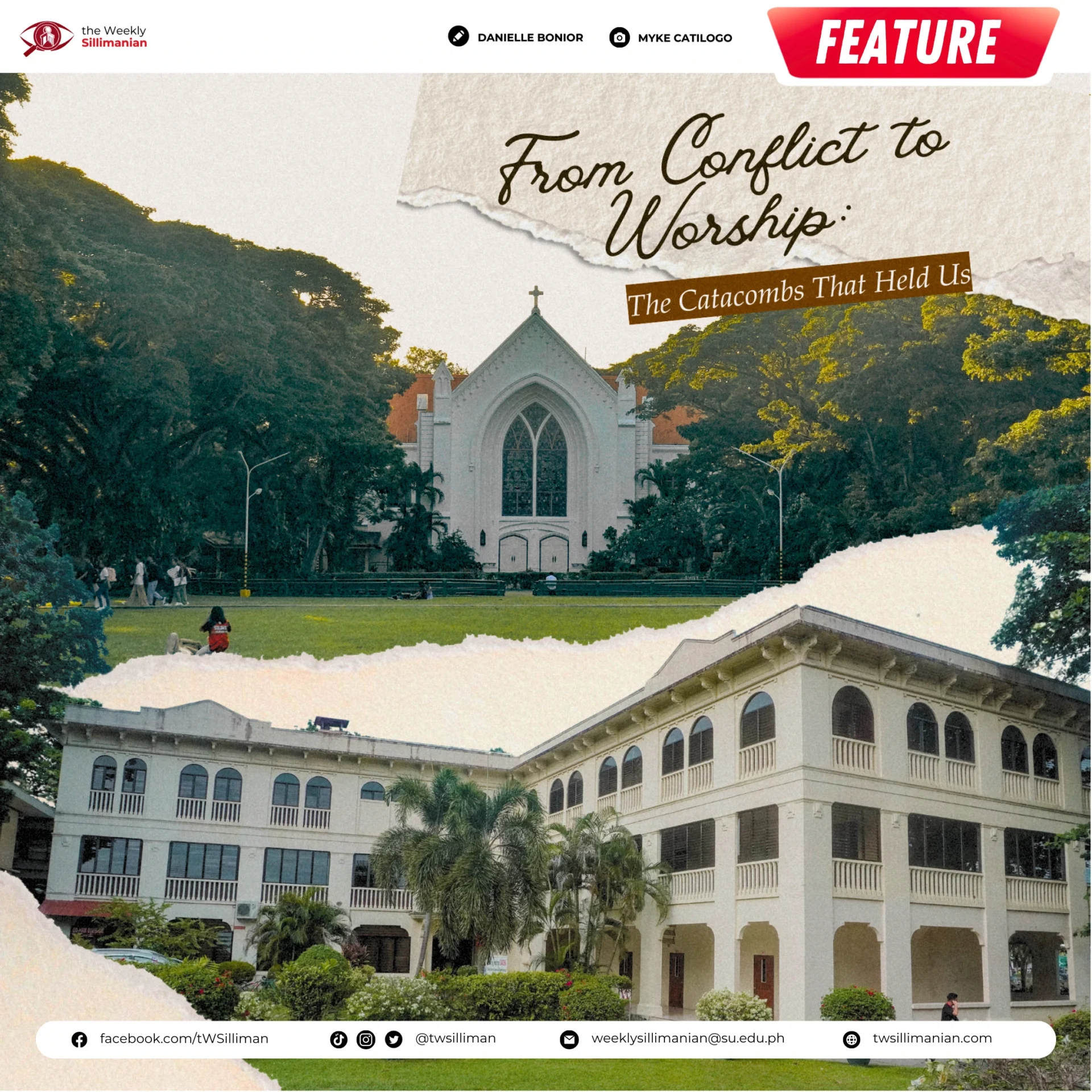

Beneath the chancel of Silliman Church, where hymns rise and sermons resound, a quiet echo fills the deep. Unseemly and subterranean, the space below whispers of psalms refusing to lie still—as remnants of words written and sung cling to dilapidated walls. These walls remember unrest and resounding joy. Beneath the Silliman church lies a secret, a tomb, which holds the Silliman spirit.

This capsule of space and time is the Silliman church’s catacombs, a place borne not of bones but of voices, of movements both hidden and bold—a story of the convergence of subversion, of creativity and community.

More than a meeting space; the catacombs became a living archive. During Martial Law, books were safeguarded here, shielded from potential destruction.

Prof. Carlos P. Magtolis, Jr., historian, 2016 Silliman Church administrative officer, and former CAS dean, calls the catacombs more than a physical shelter. “During Martial Law, they were used as a clandestine gathering space,” he says.

Here, freedom was spoken in hushed tones, nestled safely beneath the towering sanctuary above. Meetings, “teach-ins,” and whispered plans breathed life into what Magtolis called “a lively place.”

The Catacombs Amidst Martial Law

Under the suffocating grip of Martial Law, the Philippine Constabulary, headed by Fidel Ramos, imposed strict surveillance over Silliman University. Organizations were banned, and students found themselves muzzled. The Weekly Sillimanian, the student government, and all other groups were silenced.

Only one organization was allowed to operate—the Christian Youth Fellowship (CYF)—as Ramos was a member of the UCCP Ellinwood Church. But even in the catacombs, freedom of expression was dangerous. “You couldn’t trust anyone,” Asst. Prof. Oyen Alcantara, head of the Psychology Department and Coordinator for Campus Chaplaincy and Student Ministry in 2008, recalled. Informants were everywhere and open dissent led to dire consequences.

The catacombs in the 1970’s mirrored the chaos above ground. While the military’s barbed wire surrounded the campus, students went underground to reclaim their voices. It was here that songs of disguised dissent were sung, their melodies “hidden messages” against the regime. Mr. Moses Joshua B. Atega of the Cultural Affairs Committee recounts how acoustic nights filled the space with strumming guitars and harmonized voices.

“Folk songs and those from pop culture, such as the Beatles, were very popular during the time. Actually, a song that they sang which subtly promoted activism was the Beatles’ ‘Let It Be.’” he said. Over time, this calculated subtlety earned enough trust from the military for Silliman to regain its student government in 1981.

Worship, Art, and Music in the Underground

Yet, these catacombs were not always political. Long before the military encroached upon the campus, they served as a sanctuary of camaraderie. Alcantara calls the space “a fellowship room” born out of necessity. “For a while there was no facility where young people could gather,” he explains. Slowly the catacombs became a hub for worship, art, and music.

The catacombs hosted youth “contemporary worship” and intimate gatherings for musical performances. These were called “Catacomb Specials,” the forefather to UCLEM’s Acoustic Night. In fact, world-class performers such as Junix Inocian started performing in the catacombs—Inocian who later became a global theater icon, whose songs borne in the catacombs spoke of love and resistance.

Atega also vividly described the atmosphere. “Every Friday, students would gather there, sharing poetry, music, and even love notes on the wall,” he said. “It was freedom’s pulse, even when freedom felt dead.” Through generations, the walls of the catacombs became canvases for expression—painted blocks filled with declarations, sketches, and verses.

In the 70’s and early 80’s, the catacombs featured an expression wall. Fondly called “penta blocks,” these one square foot brick blocks could be rented for one peso and fifty centavos.

Students were willing to shell out the amount, not only because it was a space where they could express their advocacies and angst, but also because it was for a good cause: it generated funds for the youth ministry of the church.

Lovers would also rent a block, and leave their love notes there. Those who wanted to speak of freedom during a time of great censorship and restraint would impart their poetry and artworks on the “penta blocks.”

“During 2001, the Order of the Golden Pallet, the official visual arts group of Silliman University, decided to revive the penta blocks. They sold the blocks to visual artists and other students for 50 pesos,” Atega added.

The idea of the catacomb penta blocks was a paradox: carving permanence into a space meant for the transitory.

The Catacomb Languishes

However, the catacombs were not immune to neglect. After Martial Law, the vibrant tradition faded and only the echoes of its cultural significance remained. Attempts at revival emerged sporadically, like the “Honesty Coffee Shop” initiated by Rev. Haniel Taganas in the 2000’s, where students brewed coffee, made their own change, and honored an unwritten trust. Even this initiative was short-lived, undone by structural issues and loss of momentum.

Atega mourned the loss of these physical memories—the painting over of some of the penta blocks—to misguided maintenance. “We painted over our past,” he said. “We erased what should have been preserved.”

The preservation of this history faltered in later years. Magtolis recounted with dismay how the catacombs fell into neglect, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. “During my time as an administrative officer of the church, we examined documents stored there—financial records, theses, annual church reports, all carefully filed. But later, I learned they were burned,” he said.

Today the catacombs are in rack and ruin. Flooding and disrepair have made the space inaccessible. Atega laments the indifference. “It’s still there, the space is there,” he says. “But it will take another youth group to bring it back.”

Magtolis, too, sees potential in its revival as a place where spirituality and creativity meet—a coffee shop for Bible studies, student concerts, and quiet moments of reflection.

The Catacomb Calls

The catacombs hold more than historical weight; they embody the unyielding Silliman spirit. This spirit, Alcantara reflected, can be traced through every shadowed corner of the space. “It was not open,” he said, referencing the secretive gatherings during Martial Law, “but it gave people a sense of normalcy, a chance to be human again.”

Beneath the silence, the catacombs hum with possibility. They await not just restoration but reawakening. Their story is ours to tell, to preserve, to make it relevant again. And as Atega says, “This is history we cannot erase. This is the bond we share, the legacy we inherit.”

If the walls could speak they might ask only this: to listen, to remember, and to make sure what was once a heartbeat of freedom does not fade into silence.