By Danielle Bonior

What does the “belen” mean to you?

For many, what comes to mind is a tender tableau vivant. Families portray the nativity of Jesus by their own preferences, traditions, and personal regional culture. Whether it be porcelain, hay, wood, or concrete, there are universal elements to the Filipino belen: the likeness of Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus, often set against a backdrop of stables and stars.

Yet, in my family, the belen has a different face, one rooted not in hay but in soil—not in stables but in the rhythm of seasons.

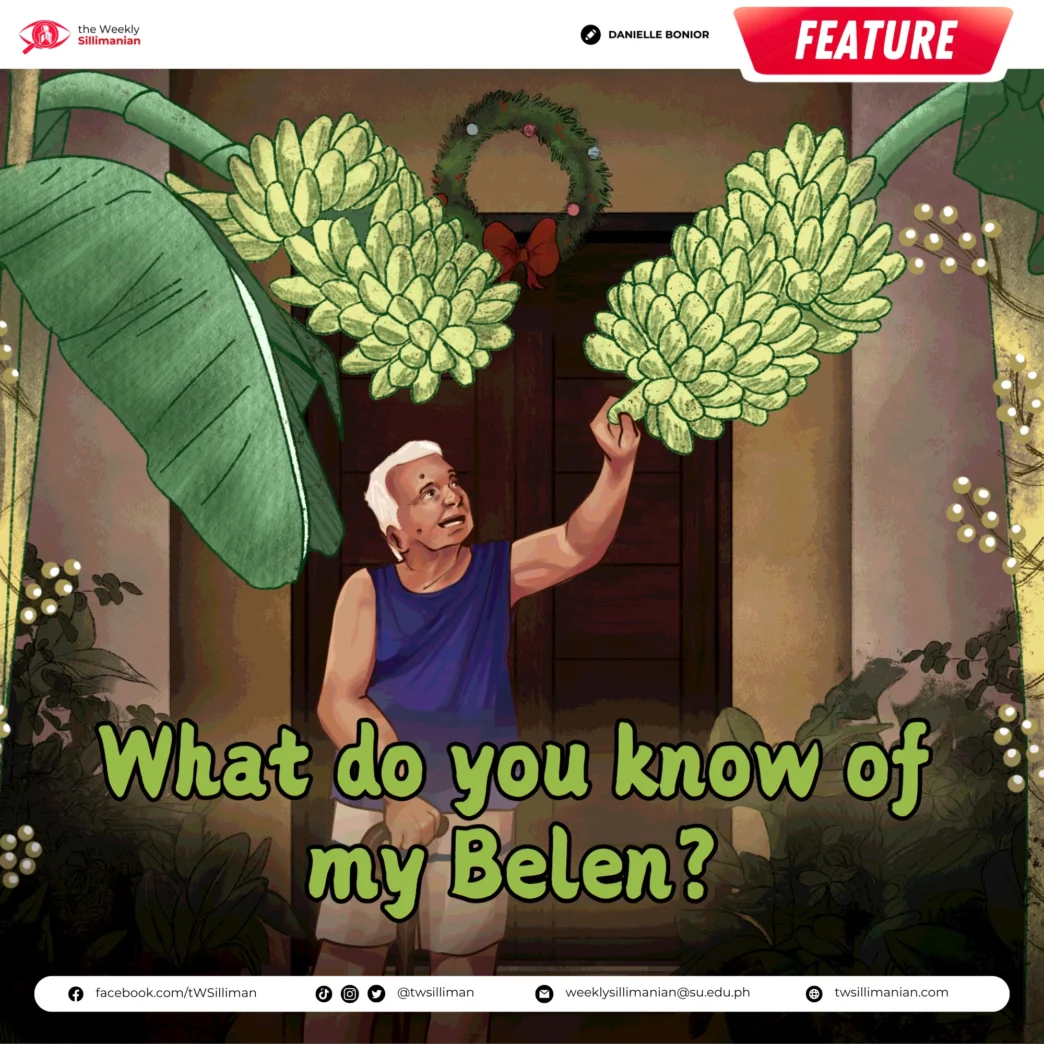

For us, the belen is two banana plants, freshly cut and carefully chosen in October with their finest fruits still clinging to the stalks. When the first hint of Christmas carols color the December breeze, the banana plants are fastened to the main entrance of our home, facing each other like old friends—or perhaps new lovers at home’s doorstep.

I once asked my mother, a local of Ajong, Sibulan, when this tradition began. She paused, combing through the cobwebs and frost of memory, and reminisced, “It’s always been this way. Even as a child, I saw my grandfather out in the fields every October, scanning the banana plants for the ones with the most promising fruits.” By the end of November, he would cut down two banana plants and position them facing each other at the entrance of the house. Over time, the weight of the ripening fruits would cause the bunches to bow, their tips bending toward each other until they formed a heart.

But this belen isn’t just about appearances, there are rules. First, only the healthiest banana plants are chosen, their fruits free of blemishes and pests. Second, the bananas must ripen as New Year approaches, their colors shifting from bright green to dark green to golden yellow. Third, on New Year’s Day, the fruits must be plucked one by one from the still-standing pair of banana plants, with each banana handed to a neighbor, relative, friend, or loved one, and some kept. Lastly, when all of the ripe fruits have been gifted, the whole banana plant must be returned to the Earth, without snapping the peduncle.

This act of sharing, of community, of care, of love, and of respect to life embodies the Sibulan Christmas spirit, a gesture of gratitude to God for the bountiful blessings of a year’s past, and a prayer for a productive year to come.

My mother speaks of this tradition with reverence, “I hope you’ll continue this,” she says, “and that your children will, too.”

But her words leave me uneasy. Will there still be Visayan banana plants for my grandchildren to cut? Or will this ritual, so deeply rooted in the land, wither in a world paved over by progress?

What will happen to our belen—this humble offering, this quiet symbol of hope and abundance? Will it become just another tale we tell, like the stories of rivers that no longer run or fields that no longer yield? Or will it slip from memory altogether, a tradition lost to a future of genetically modified bananas decapitated en masse, akin to Midas gold—glimmering yet disembodied. A future where imported bounties prevail over local produce, where foreign fruits invading our supermarkets become the only choice?

In this reality, it would be virtually untenable to continue this tradition of belen—even if my great grandchildren would want this, could appreciate this.

Will the belen of my mother’s grandfathers and the grandfathers before him become relegated to subtext in a niche book, a relic of some pictures and texts in a museum, or a sweet reminisce of generations past in idle Christmas conversations? Will this be the reality in a new Philippines, where my descendents no longer need to wait for fruit to ripen?

How long? How much time is left?

Do you know of my belen?